(Note: this is the second in a series of posts about collaboration. There’s a little introductory bit on the first one. If you’re into that kind of thing, by all means check it out there.)

So. Yeah. Co-writing novels.

Not counting the Illuminatus!-inspired adventure novel about public-private key encryption and oppressive MIBs my best friend and I noodled around with in high school (and really, it’s more dignified for all of us not to count that one), I’ve collaborated on three full-length novel projects with other people. Two of them worked out (more or less). One didn’t.

One small caveat before we start: This kind of thing has as much to do with who you’re working with as how you’re working. The stuff that worked for me may not work for you and whoever you’re writing with. On the other hand, I’m pretty sure the ways I went wrong will effectively hose anyone.

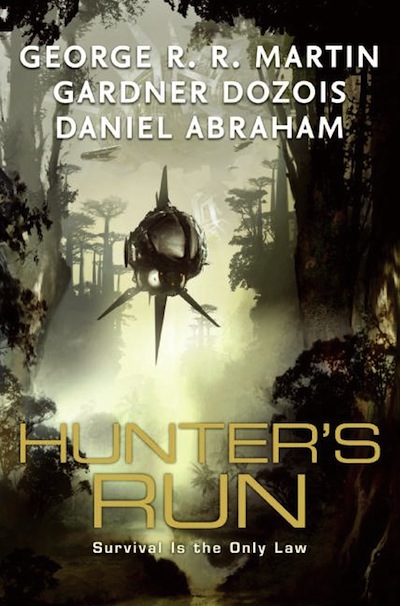

No, Hunter’s Run isn’t the one that got away.

Back when Ellen Datlow was putting out Event Horizon (her online gig before Scifi.com), she had this thing where she picked four authors, slapped them together, and had them write something. It was very structured. Three rounds, something like five to seven hundred words each, with a grand total total somewhere in the respectable short story length. As a method for composing fiction, it was somewhere between a dare and a parlor game. I signed on, and got paired up with Walter Jon Williams, Sage Walker, and Michaela Roessener. We put together an idea for a science fiction retelling of Romeo and Juliet on a world where bullfighting and hand-to-hand martial arts had joined up, with Cretan bull-dancing on the side as a cross between rodeo clowning and the Masons. We planed the whole thing out in great detail before we started. The process, as I recall was something like this: Writer 1 does their bit (yes, I’m one of those politically correct they-singular people—move on, there’s nothing to see here), then sends the scene to the other three who comment. Writer 1 makes any changes that seem appropriate, and tags out. Writer 2 does the next scene, repeat as needed until conclusion. We utterly ignored the wordcount limit, so we wound up with something more like a novella.

That wasn’t the failure. The story came out pretty well. But then we decided to build on it. We planned out a fantasy trilogy riffing on Antony and Cleopatra, talked over the big arcs, sketched it out, and then we went at it. We weren’t constrained by wordcount, we weren’t held to the idea of writing it one scene at a time like putting bricks in a pile, we could work in parallel. We had the freedom to run it any way we wanted. Turned out, that was what killed us.

Understand, we’re talking about four talented, professional writers who had all worked together successfully on the project’s immediate precursor. It wasn’t that we couldn’t work together. It was that when we lost the rigid, game-like structure, we all started wandering off, exploring the parts of the world and story that turned our particular, individual cranks, and the cohesion we had when we were tied to the next scene, then the next then the next went south. Eventually, we just stopped.

The next project also started with something shorter. George RR Martin took me out to dinner one night—Chinese if I remember correctly—and with perfect seriousness said “So, Daniel. How would you feel about a three-way with two old, fat guys.”

Turned out that he and Gardner Dozois had a story that Gardener had started when I was still in grade school, and George had picked up when I was noodling around with that Illuminatus!-inspired thing I was pointedly not mentioning before. They’d run it past folks every now and then, and did I want to take a look, see if I could finish it up.

I could. That turned into a novelette called Shadow Twin. It was a profoundly different project. I hadn’t been introduced to the idea of multiplication when the story was first conceived. Two-thirds of it were already written. And neither of my collaborators wanted to get in my way. I had most of a story, some ideas about where I might take the ending, and a free hand to do whatever I needed to, so long as it worked. I cut out a bunch of what they’d done, added on my bit, and voila. It sold to Scifi.com (Ellen Datlow again), and was reprinted in Asimov’s and a collection of the year’s best short novels, and as a chapbook from Subterranean Press.

And then, we decided to go for one more. There were bits in the novella that seemed like there was more story to tell, places where some piece of business got rushed to fit in a sane wordcount, and the instinct (especially with George) that there was more story to tell.

So we threw the whole thing out and wrote it again as a novel. It was retitled Hunter’s Run. Unlike the post-Tauromachia project, the story was already set. We’d told it once from start to finish, and the expansions we did were to add a framing story that gave the action more context and explicitly set it in the universe of Gardner’s solo novel, Strangers. Very little planning was necessary, and most of the disagreements we got into were over style. (Mostly, I cut out Gardner’s descriptive passages, and then he put them back in.) As the junior member, I got to do the absolute last-pass line edits and polishing because that’s part’s a pain in the ass. The book that came out didn’t read like one of mine, one of George’s, or one of Gardner’s. By putting the story through the blender, it had taken on a voice of its own. Plus which it got a starred review in Publisher’s Weekly, the American Library Association called it the best science fiction novel of 2009, and it was compared to Camus by Entertainment Weekly and Joseph Conrad by The Times (not the New York Times, the other one). So even if I fought Gardner over every adjective, I still have to call this one a success, right?

And then there’s the third project.

So, .com-era joke. Ready? Two guys who knew each other in high school meet up in silicon valley during the boom.

“Hey, Dave,” says one. “What’re you up to these days?”

“Can’t talk about it. Nondisclosure agreement. You?”

“Yeah, I can’t talk about it either.”

“Still. Good seeing you. We should have dinner some time. Not catch up.”

So I can’t talk about this one in detail. Nothing personal. Just business. But I can talk about the process. For about a year, I met with this guy once a week. We started by sketching out the rough outline and arc of a story, much like Walter, Sage, Mikey and I had back up in the one that got away. But then we broke it own from there. How many chapters, what happened (roughly) in each chapter, who the point of view characters were. Then each of us would write a chapter, give it to the other one to edit and comment on, stick the two finished chapters on the back of a master document. Every couple of months, we’d revisit the chapter outline and add, cut, or change it depending on what we’d discovered about the story in the writing of it.

Like the Tauromachia novelette, this was built in a scene-by-scene format, with each of us aware at all times of what the other was doing and with an editorial hand in the line-by-line work the other was doing. A lot of what we did weren’t things that I would have reached for on my own, and the guy I was working with had to change a lot of things about his style to fit with mine. The book we came out with . . . well, we should have dinner sometime, not catch up about it. But I was and am quite pleased with the project, and I count it as a success.

So, to sum up: The times that co-writing a novel has worked for me, it’s had 1) a very clear, structured story with a lot of fine-grain detail (either as an already-completed story to expand or a detailed and frequently-revisited outline), 2) a lot of feedback between the collaborators, 3) a willingness on the part of all the writers to have to project not be an ongoing act of compromise and not exactly what they would have written by themselves, 4) an explicit mechanism for text written by a particular author to be handed over for review and editing by the others, and 5) deadlines.

I’ve learned a lot from the collaborative novels I’ve written. If it’s the kind of thing you can do, it will teach you things I don’t think you can learn otherwise, both from being in the working company of other writers and by being forced—time and again—to explain yourself.

And seriously, if it’s not the kind of thing you can do, avoid it like the plague.

Daniel Abraham is the author of the Long Price Quartet (A Shadow in Summer, A Betrayal in Winter, An Autumn War, and The Price of Spring, or, in the UK, Shadow and Betrayal & Seasons of War) as well as thirty-ish short stories and the collected works of M. L. N. Hanover. He’s been nominated for some stuff. He’s won others.

Shadow Twin‘s an excellent book.

I know that the actual tools of collaboration on Wild Cards are, or at least have been, very traditional. I’m going to guess Shadow Twin, too.

But this third collaboration you’re working on, are you just e-mailing chapters back and forth, or are you using any of the new-fangled collaboration tools out there — Google Docs (I know Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette used it for A Companion to Wolves), Etherpad, or (heaven-forfend) Google Wave — to help speed it along?

Wave currently doesn’t have any good exporting method, so it’d be awkward to use for any lengthy writing. That said, for the planning stages of a collaborative story, it could be a pretty fantastic tool.

I’m seriously going to have to pick up Hunter’s Run. It sounds like a great book.

It’s interesting to get an insight into those collaborations. I’m getting ready to join a collaboration right now myself and I’m going to keep these ideas in mind.

Hunter’s Run is a great book. Thanks for the insight into the process behind it’s creation.

Daniel,

With HUNTER’S RUN being a semi/sorta sequel to Gardner Dozois’ book STRANGERS, does Gardner himself or any of you guys have plans for writing further stories set in the same universe or setting? …Or, moreover, since you have been part of the writing team on this book, could “you” potentially write a story set in the world of HUNTER’S RUN if you wanted to? Or would that be too close to being fan fiction? :D

Thanks!

P. S. HUNTER’S RUN is the first thing I ever read from you and it introduced me to your work. Thank you!

You know, it’s funny. Most collaborative stories I hear about are written like this. It’s the “old school” style of collaborative writing, where people write stuff and send it back and forth, taking turns.

It’s how I used to do collaborations, too, back when I wrote on Internet fiction forums such as Superguy back in the ’90s. But from where I am now, it seems very old-fashioned, kind of like collaborating by typewriter.

My generation and onward basically grew up (if you can call it “grew up” when technically I only started doing it in college) on Internet role-playing. Where you get together in a text-based environment, each playing a character of your own, and have your character interact with other peoples’ characters.

In the last few years, tools (such as EtherPad) have come out to make it possible to write stories together, in a collaborative process not unlike Internet role-playing. You do it in the past tense, with proper punctuation and quotation marks, and you can go back and make changes if you think something came off wrong, but for all that it’s very much like that same roleplaying process. (I’ve even co-written some City of Heroes fanfic that way with Mercedes Lackey.)

That’s how I do a lot of collaborative writing these days: I make up my characters, my co-writer makes up his, and we put them together with a general idea of what is going to happen and then see how it does.

It doesn’t always end up being great art, and how well it works depends on how well the other writer and I are able to mesh our visions. (I’ve been accused more than once of being “too overbearing” and forcing the plot to go where I want it to go without giving enough consideration to the other guy.) But it seems a lot more immediate than the old method of shipping large chunks of text back and forth.

Sometimes it can cause problems, when you can see (and fall in love with) the scene going one way, and the other writer has very different intentions. Sometimes I have to remind myself that I’m not the only one writing, and if I wanted the story to go a certain way I could have written the thing all by myself.

But on the other hand, it can be a lot more rewarding than just writing by yourself, because it introduces that element of uncertainty: you really don’t know how it’s going to go because you’re only partly in charge—the other half of the story is being decided by someone who isn’t you, which means you’re invariably going to be surprised. And that surprise is often good, and can lead to things happening you never would have thought of by yourself.

For some reason, I don’t hear of much professional fiction being written that way. Even writers who live together, such as Sharon Lee and Steve Miller, basically collaborate by taking turns in the hot seat rather than by actually writing together at the same time.

I can’t help thinking it might be interesting if someone were to give it a shot. On the other hand, perhaps there are good reasons nobody’s tried it like this yet.